Ayesha Harruna Attah recounts a voyage of discovery that begins from a point of ‘cultural envy’ – a realisation of how little African writers know of their myths, the rich archive of knowledge of the continental pantheon – and ends in an understanding of a ‘shared continuity’ over millennia of African cultures, histories and philosophies.

I first heard about Cheikh Anta Diop in college – not in a history class, not in an anthropology class, not even in the science classes that could have mentioned his contributions to physics. His name came to me on a piece of plastic spinning on a cheap CD player I bought from a department store in New York.

I was intrigued by the Franco-Cameroonian sister-duo Les Nubians ever since I heard their hit song “Makeda,” so their second album, One Step Forward, was one of the first CDs I ordered from the BMG music service, a catalogue popular in the early aughts – buy 12 CDs for the price of one (a pitfall for many a college student possessing a bank card for the first time in her life). The last track, at eight-plus minutes, was an homage to Diop, titled “Immortel Cheikh Anta Diop”. It lulled me with its beautiful soulful hook, with its delicate xylophone, with its dreams of an Africa united. It wasn’t a track to be taken lightly and, even though my French was then rudimentary, I didn’t miss its poetic pleas for Diop to still be alive. At the time, my 18-year-old curiosity didn’t take me beyond the words of the song, but I would discover Diop again, a few years later, in the country of his birth.

Visiting the Napier Museum with me in Trivandrum, the political capital of Kerala in the south of India, were an art historian, a fellow novelist, and a poet. We belonged to the same generation, give or take a few years: born in the 1980s, came of age in the 1990s. As we walked from glass-caged artefact to artefact, my new friends dazzled me with the knowledge of their traditions, of their gods, of their history. From their descriptions, many of the mischievous gods, the demon gods, are dark-skinned. Of course, I remarked, trying not to bristle at how long prejudice against dark skin has existed, and how pervasive it is. But Shiva, they said, is one of the most important gods, and is considered so black, he becomes blue. We walked by Shiva in his many incarnations: half-man, half-woman, with womanly hips and one bulbous breast; Shiva mid fierce-dance pose, the dance that destroys. The art historian had to leave for another function, so the poet stepped in and what she lacked in historian’s precision, she made up for by keeping me riveted with her poet’s eye and ear. She regaled me with stories of the Ramayana, one of the Indian subcontinent’s largest epics, and one she draws from and subverts in her own work.

This was not the first time I had experienced cultural envy. A friend from China could easily recite her ancient knowledge, which invariably seeps into her work as a filmmaker. I would be hard-pressed to find a European writer without knowledge of Greek or Roman mythology. It made me wonder: how many African writers know of our myths, and if anyone still cared about them and the knowledge latent in them? I had only begun, in the past 10 years, to learn not only about the Egyptian, Yoruba and Igbo pantheon, but also more about the continent’s history.

I was not taught this expansive history in school. Picture a fictional elementary school in any large city on the continent – Accra, Lagos, Kampala… Now, visualise a teacher who wants to give her pupils a solid, all-round education. In a literature lesson, she tells her students a creation story from one of the earliest African civilization: before people were created, there was chaos and, within the depths of that primordial soup, intelligence began to gather to form the first signs of life. This kind of thinking preceded other creation stories that envisaged a creator god who breathed life into living things.

A few days later, imagine the parents of the newly aware students at this school banging on the principal’s door, demanding an explanation for why their children are being made to swallow outdated/subversive/demonic ideas. These children, deprived of such knowledge, easily slip into and own worldviews, such as Christian or Muslim. There they stay, unless they question, start searching, an understanding that all people have stories and the oldest live on the African continent. It wouldn’t be surprising that the children in the box think that everything African is outdated or demonic or that Africans have never created anything of value. And even when they do identify as African, their vision of what that is is often myopic, beginning with European contact.

I was a child in the box. In my early days, I hankered to be Christian or Muslim, or more than just 50 per cent Ashanti. While in college, my awakening began when I started questioning religion. Growing up with a Muslim father and a Christian mother, there were points of intersection, but there were clear, existential divergences. For instance, my father would go to hell if he didn’t accept that Jesus died to save his soul. I knew both Islam and Christianity had been forced down the throats of my ancestors, and none of it seemed right or fair.

The questions kept piling up and it made sense to search for answers. Early on in the voyage, I met a traveller who would teach me that to find solutions to the problems that currently plague us, Africans should consider their history as deeply and as widely as possible. This traveller would introduce me to the work of Cheikh Anta Diop, a trailblazer for learning to search within ourselves and our land as Africans, in order to plough forward less blindly into the future.

The questions kept piling up and it made sense to search for answers. Early on in the voyage, I met a traveller who would teach me that to find solutions to the problems that currently plague us, Africans should consider their history as deeply and as widely as possible. This traveller would introduce me to the work of Cheikh Anta Diop, a trailblazer for learning to search within ourselves and our land as Africans, in order to plough forward less blindly into the future.

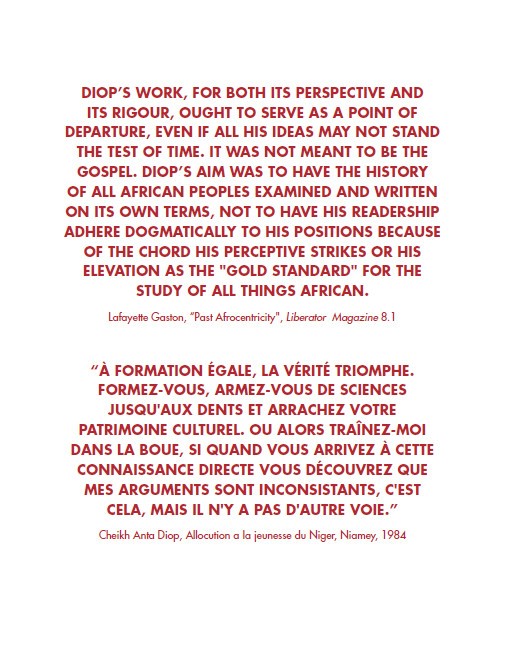

To write my first novel, I went to Senegal to the Per Ankh program for young African writers. There, I was mentored by Ayi Kwei Armah, who had been inspired by the work of Cheikh Anta Diop, as he himself puts it in The Eloquence of the Scribes: “For anyone conducting research on African literature, Senegal was an important place to come to. Here was the home of two iconic intellectuals representing schools of thought at the negative and positive extremes of the debate on the nature of African identity, history, philosophy, culture and literature. At the negative extreme stood Senghor of negritude fame. At the positive extreme there was his younger opponent Cheikh Anta Diop…” Armah wrote that Diop’s approach to the study of Africa’s history – the holistic approach – was a model that could be carried over to other disciplines.

Also at Per Ankh, I would meet other travellers, one of whom gifted me Diop’s African Origin of Civilization. This book introduced me to the idea of a shared continuity across African cultures, a theme would come to influence my work and contour the worldview taking shape in me. Civilization or Barbarism became another seminal work and invaluable reference book. In the introduction to African Origin of Civilization, Diop states emphatically: “The ancient Egyptians were Negroes.” Diop’s scholarship involved history and science and thorough research. When he quoted Herodotus – “It is certain that the natives of the country are black with the heat…” – he also conducted experiments – melanin tests, blood group analyses, osteology – to back this up. I don’t see Diop’s work as a suggestion to blindly return to Egypt to take back what was ours (We were kings and queens!). It is more a call to objectively place Egypt in its context, and to use its ancient knowledge to orient us forward.

As Diop himself wrote in Civilization or Barbarism: “The historical conscience, through the feeling that it creates, constitutes the safest and most solid shield of the cultural security for a people. This is why every people seeks only to know and to live their true history well, and to transmit its memory to their descendants. The most essential thing is for people to rediscover the thread that connects them to their most remote ancestral past.”

I try to apply the knowledge gleaned from Diop’s work in my daily living and in my writing. When I set a character in pre-colonial Ghana, for example – a time when most European accounts reduced Africans to little more than greedy barbarians – I write with knowledge that the character is not rootless. That even though we may have forgotten, through our veins course millennia of culture, of philosophy, and history. And even though we have been fragmented, and made to believe we have no past, bits of consciousness still exist and can be awoken and brought together again.

[hr]

This and other stories available in the new issue of the Chronic, “The Invention of Zimbabwe”, which writes Zimbabwe beyond white fears and the Africa-South conundrum.

The accompanying books magazine, XIBAARU TEERE YI (Chronic Books in Wolof) asks the urgent question: What can African Writers Learn from Cheikh Anta Diop?

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop, or get copies from your nearest dealer.

[button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/chimurengashop” color=”red”]Buy the Chronic[/button][button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/subscribe” color=”red”]Subscribe[/button]