Ayi Kwei Armah traces the contour of an old conflict and a lifelong struggle for the birth of the beautyful ones.

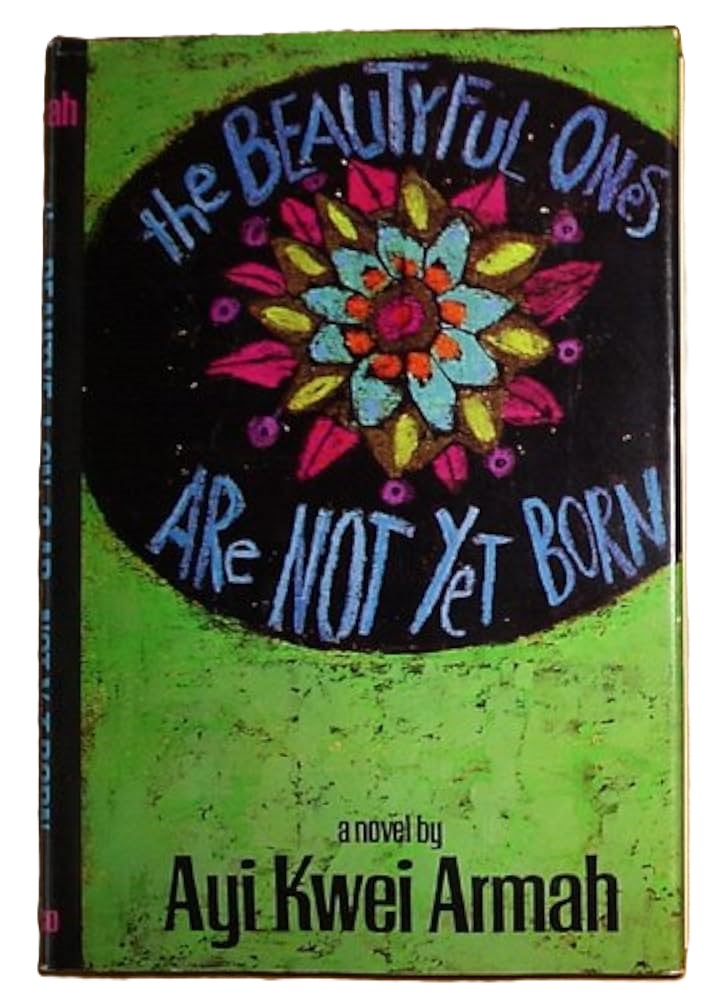

The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born

Ayi Kwei Armah

Houghton Mifflin (1968)

A few reactions to my book, The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born, have been bluntly hostile, the most extreme being the attack Chinua Achebe, the Igbo novelist, launched against the book and its author shortly after its publication.

Speaking at Harvard University, USA, at a time when I was, I think, in Mtwara, near the Tanzanian border with Mozambique, Achebe built his condemnatory argument around an astonishing claim: he had discovered a quote “somewhere” in which I, Armah, said I was not an African writer. For good measure, he implied that I had said so in an effort to please Western audiences.

I wrote to Achebe asking where he had found the supposed quote, since, contrary to scholarly practice, he did not indicate his source. He didn’t answer my letter. I wrote him a second letter to tell him what I thought of such tactics.

I did eventually have a chance, on a visit to Nigeria, to ask him face to face, before a small group of peer academics and writers, where he got the quote. His answer, that he didn’t feel obliged to disclose his source, told me more than I wanted to know about Achebe’s scholarship and his deontology.

In case anyone is tempted to wonder whether the considerable animus Achebe has displayed toward my work and me has personal roots, let me state unequivocally that there is no personal basis for any ill feeling between us. There is no quarrel either, unless the sound of one person persistently backbiting another in public can be called a quarrel.

My relationships with writers from everywhere are generally cordial. Among African writers, the one I was closest to was the late Sembene Ousmane, who was not just a friend but a companion and cofounder of PER ANKH, the small African publishing cooperative that now handles all my books. I can, in fact, think of only one writer who has any reason to feel a deep personal hatred toward me.

My unforgivable crime? Around the time when I finished writing The Beautyful, the writer in question, along with a small group of friends, thought to do me a huge favour by offering me part ownership plus the editorship of Ghana’s biggest and most powerful newspaper, the Daily Graphic.

Had I accepted the offer, it would certainly have made me a big shot. Trouble is, I have never wanted to be a big shot, not even a medium shot. I want to be myself, period. I knew I was too poor to buy a whole newspaper, or even one-fifth of it. I knew the others in the ad hoc group were no richer than I.

When I asked where such a gathering of intellectual brokemen was supposed to get the money for privatising such a big paper, I got an explanation: a well-placed contact in the state bank was ready to advance us the necessary capital. All we had to do was to sign here and then here.

The scheme was elegant in its duplicity. We were going to steal, I beg your pardon, borrow, public funds with which to privatise public property. After that, as editor, it would be my duty to write soul-stirring pieces in favour of good governance, against corrupt practices, all in support of the military government that overthrew Kwame Nkrumah. I refused that generous offer, no doubt earning myself the mortal enmity of a disappointed man.

But back to Achebe. His attack was off-target, awkward and mendacious, but the fact that he felt a need to mount it at all might be rooted in something more serious than the concern of an alpha male guard for African writers on the Heinemann publishing plantation eager to expel a potential intruder into his given territory.

He need not have bothered. I never intended to settle on that patch, since I have always wanted to find, or failing that to help create, an African publishing home for my work. I am glad to say that since the founding of PER ANKH, the hurdle lies behind me.

Achebe is 10 years my elder. I first met him when I was a Harvard senior and he a writer on a lecture tour. At the time my focus had shifted away from literature, because I had moved from English to Sociology. I was also helping to found the Association of African and Afro-American Students, and, most crucially, negotiating with Angolan observers at the United Nations mission to see if I could go to work for the African liberation movement in Southern Africa.

The Association of African and Afro American Students did get off the ground before I left Harvard, but my attempt to work for the African liberation movement ended in complete failure. The point here, however, is not my success or failure in fields other than the writing of fiction. It is that the life choices I made at that time – to make a vocation of the African liberation struggle, and to go where I had been assured I could get training for the purpose – would have been utterly impossible had I not already been in the habit of identifying myself not as a member of a tribe or a colonial state, but as an African.

Seeing myself as an African, I had thought it natural and logical to choose work that, in my estimation, would help to bring about the necessary condition for the creation of a new society in Africa: continental unity. I looked forward to meeting and working with other Africans from colonies called Rhodesia, South Africa, Angola, Mozambique, and with volunteers from other African countries, working toward the same purpose – the unity of a people determined to create a viable continental home – together.

Failure is loss, of course, but my failure to reach the instrumental goal of participation in the machinery of liberation did not mean a loss of the African identity and vision that had energised the search for the liberation movement in the first place. My challenge, after failure, was to figure out how to invest that African consciousness in any work I chose to do. I chose writing, and in doing that work, I have sought consistently to project the only vision I think worth projecting: an African vision.

There are persons who think it is impossible, even presumptuous, for a writer to attempt to project such a thing as an African vision. I wish them luck in their tribal or colonial national identities, but I do think the projection of a continental identity, even if that identity has no visible ceremonial insignia, tribal scarifications, sacrificial oaths, death squads, armies, police forces, customs barriers, prisons, anthems and artificial frontiers to signal to the brutalised world that it exists, is a worthwhile challenge to the artistic imagination. No innovative intellectual need fear such a challenge.

I have accepted it, and found that though it demands a lot of effort, especially in rigorous scholarship, it also offers tremendous rewards in the form of contact with the work of such profoundly creative thinkers as Theophile Obenga, Cheikh Anta Diop and Chancellor Williams, all bearers of insight and inspiration.

Since I try to write as a disciplined practitioner of a millennial craft, I make a deliberate, sustained effort to have my writing express the gentle thrust of that acceptance. My writing might be inspired at times, but the inspiration comes not from palm wine or yamba, and definitely not from heaven or hell. It comes from knowledge acquired through regular, systematic research.

If the African world I want to work for were here now, I would be writing this, and you would be reading it, in an African language. I accept the sense of failure involved in my writing in a language slave raiders brought to our continent. I see it as part of my responsibility to help in the work of remedying that linguistic anomaly.

I would be delighted, if I met companions working in that direction, to participate in the intellectual groundwork needed to create an African language for a future of our own. Until then, I can do more of the necessary research that future creators on that path will need, alone or with companions if I find any.

I accept the stultifying need to carry travel documents and identity cards when moving from one colonial state in Africa to another, but I would be overjoyed if tomorrow, in an access of common sense, bureaucrats and politicians all over our continent abolished the stupid borders left here by ghosts from Berlin. Again, if I met companions working to bring about such a borderless state of affairs on this continent, I would be ready to work with them, full-time, for no salary.

Meanwhile, I write. I hope to write my fiction and expository prose in such a way that those who read it will see how idiotic our present ways of hand-me-down living are. If images of disgust can help sharpen that awareness, I will not hesitate to use them, and will gladly welcome the disapproval of those who think loving Africa requires us to praise the current mess. Working this way, I invite anyone who feels he can achieve some purpose by pointing fingers at me and calling me anti-African to continue doing his work.

Where I live, I arrange with friends to teach younger writers to sharpen their planning skills, to learn their craft systematically, and to take control of the technical and financial aspects of their work. I research useable information on all of Africa’s space and time, in the hope that some day, if any movement or group, having the energy for motion but unsure of its direction, seeks pointers as to how to work, or govern, or live according to regenerative African values, they can find the information available, ready to serve them.

In short, I am ready to join with anyone interested in doing the necessary work of cultural connectors; the work that could ensure the birth of the beautyful ones. Call it foreplay, or, if you prefer, forework.

This story, and others, features in Chronic Books, the review of books supplement to Chimurenga 16 – The Chimurenga Chronicle (October 2011), a speculative, future-forward newspaper that travels back in time to re-imagine the present. In this issue, through fiction, essays, interviews, poetry, photography and art, contributors examine and redefine rigid notions of essential knowledge.

To purchase in print or as a PDF, head to our online shop or visit Chimurenga Factory at 157 Victoria Road, Woodstock.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work.