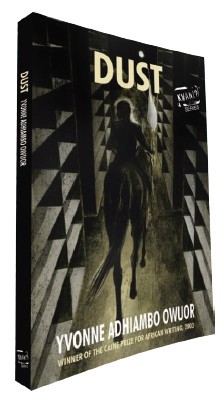

by Parselelo Kantai

Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor

Kwani Trust, 2013

It may have been the economist David Ndii who coined the term “the Chlorophyll Zone”. Recalling the tragic fallacy of centralised economic planning in Kenya in the early years of uhuru, Ndii describes how the drafters of that touchstone of economic planning in Kenya, Sessional Paper Number 10 of 1965, divvied up the country into a hierarchy of six agro-ecological zones.

Zone 1 was the former White Highlands, where tea and coffee, the country’s main export crops, were grown. This was the “high(est) potential area”. Zone 6, the arid country of the north that bordered the creeping Sahel, lands where “nothing” grew, was the area with the lowest potential. In between were aspirational zones, not quite suitable to the cash crop ideal, but still with potential for civilised agriculture.

This segmentation of the country was more than an exercise in economic planning. It set the stage for how the state would allocate resources in the newly independent republic. Deftly setting aside arguments for redistribution in favour of economic growth, the independent government allocated its limited resources to areas and projects that would produce high returns

“You can’t redistribute nothing,” Tom Mboya famously remarked. For the KANU government the immediate post-uhuru era was no time for soft-focus affirmative action – unless of course the aim was, to paraphrase Ayi Kwei Armah, to replace the departing mzungus with deserving Africans. For to this the true significance of matunda ya uhuru, the fruits of freedom, verily applied. Jobs, parcels of land and auctioned and abandoned properties were dished out generously to those who had collaborated with the colonial regime and had a modicum of Western education. Taking over from the departing settlers, they would later claim that they had acquired their new wealth by being in the right place at the right time. It went without saying that they were also from the right tribe, that is, the president’s.

But the Chlorophyll Zone also embraced another, bigger narrative that went beyond the boundaries of the politics of post-independence distribution. The Chlorophyll Zone, as Ndii and others describe it, is that strip of arable land that lies within 10 km of either side of the Kenya-Uganda railway. Comprising about 13 per cent of Kenya’s territory, it is farming country where permanent settlement was possible and where the civilising mission could be pursued with relative ease. It is in this Chlorophyll Zone that Christianity thrived and where, post-uhuru, tangible “development” could occur.

This is the Kenya of the economic planners’ visions – the Kenya tailor-made for modernity and investment. It is this Kenya from which emerges the official narrative of oppression-liberation-maendeleo (development). Outside it lies an area of darkness populated by stubborn and ungovernable peoples, for whom the colonial stick, rather than the carrot of uhuru, was being applied well after the mzungu had left the scene.

These people, we were taught from the earliest days of primary school, were backward, primitive. They wore shukas, not trousers. They were lazy and ate strange food. They did not go to school and they did not love the Lord. And going by the droughts and famines to which they were perpetually subjected, the Lord (and the government) punished them for their heathen ways.

On the first day of class in Standard Five, our agriculture teacher gave us an assignment: to write down what crops our people grew. When I wrote down that “my people”, the Maasai, were pastoralists and did not traditionally grow crops, I was given a proper beating. Every tribe, I was told, “grew something”. Years later, sitting in a District Commissioner’s (DC) office trying to understand why hundreds of Ogiek hunter-gatherer families had been thrown out of the Mau forest in southern Narok in the Rift Valley, I began to understand how pervasive the Chlorophyll Zone logic had become. Leaning back in his chair, the DC, a man from northern Kenya, explained that there was no room in modern Kenya for “forest dwellers”.

As long as central planners continue to favour the Chlorophyll Zone, the territory demarcated bythe colonial authorities as the Northern Frontier District (NFD) will remain outside the Kenyan imaginary. But the NFD is not the imperial outpost of Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians, a space outside a constructed imaginary of the “normal”. It actually encompasses more than three-quarters of Kenya. This is Kenya. Literary critic Tom Odhiambo regards the NFD as a metaphor of negation, a liminal space where collective “Kenyan” fears and anxieties are at once deposited and from where they emerge. And in the imaginary of the bureaucratic elite, colonial and post-colonial, the NFD is an outer darkness that generates the ultimate fear: absolute alienation. It is a place where the opposite of “eating” occurs; a place to which the Chlorophyll Zone’s dissidents are consigned, or escape, to perish, to live with their demons. This place of magical realism, where the order of things is turned on its head, is also where Yvonne Owuor constructs Dust, her penetrating narrative of loss and betrayal, her lament against a nation that has wilfully betrayed its own promise of a shared future.

Dust is set in Wuoth Ogik, to which Nyipir Oganda, the paterfamilias of Owuor’s story escapes. It is, to give it the literal Luo interpretation of Wuoth Ogik, the “end of the journey”. But it is also the beginning of a journey. Nyipir Oganda was once an important man in Chlorophyll Kenya. Proud and tall, a policeman trained in the best traditions of the force, it was he who carried the new country’s flag on a horse on the day the British left. Then Tom Mboya, a big man from his tribe and the architect of the new republic, was assassinated. Nyipir was suspected of this act of treason and exiled to the NFD.

Forty years later he is forced to return to Nairobi, the radiating epicentre of that idea of Kenya. It is here that this epic lament of a story begins, with Nyipir coming back to Nairobi to collect the remains of his son, Moses Odidi Oganda. Odidi, a young engineer-turned-robber, a former high school rugby star, the shining embodiment of middle class professional aspiration, has been mowed down in a police ambush on a Nairobi street. He had taken to crime after a terrible brush with Nairobi’s power circles. On the brink of financial and career success, “Shifta the Winger” could not countenance the dark underbelly of corruption that accompanied it. Like his father before him many years earlier, Odidi was cast out, and became an outlaw.

But Dust is not just a father’s lament. It is a quest for answers; for the big Why of Kenya’s betrayal of those who most fiercely believe in it. Nyipir may have turned his back on Chlorophyll Kenya, but that is also the place his two children went to school, went to develop an idea of themselves outside the surrealism of Wuoth Ogik. And as hard as he may try to avoid an inevitable reckoning with “down Kenya”, as northern Kenyans term it, Nyipir Oganda never completely frees himself from it. It rises to meet him in the form of this terrible tragedy. Dust also contains another kind of questing – that of Odidi’s grieving younger sister, Arabel Ajany. She is in Brazil when her brother’s death forces her to return. Back home, she must look for the meaning of her silent grief in a Nairobi that has never developed beyond anything more superficial than a functional comprehension of its naked materialism.

There is more. So much more. The language in Dust, the rolling lament that Owuor has structured so brilliantly along the lines of the Luo funeral dirge, dengo, is also a language of indictment. The finger is pointed at the owners, appropriators and managers of Chlorophyll Kenya – their rejection of inclusivity, their callous refusal to countenance anybody who refuses to speak their language of corruption and impunity.

Dust is perhaps the first novel of the Kwani generation of writers. A decade ago, this collective determined to inscribe its voice into the literary landscape with narratives that defied official discourses; that sought to roam outside the Chlorophyll Zone and challenge the thinking within it. As Kenya takes its turn in the sepia-toned festival of champagne memories and official nostalgia that passes for the ritual marking of half a century of flag independence, Dust shatters the carefully constructed mythologies of an empty heroism, and the bankrupt tunes of elite entitlements that accompany its claims of nation-building.

Kenya is a many-sided riddle. The problem was never the idea of the concocted centralising myth; it was its abduction by the elite within the Kenyatta presidency. Owuor has written a powerful rebuttal to this elite’s claims of GDP success and maendeleo progress.

Parselelo Kantai is the East and Horn of Africa editor of The Africa Report. He also writes for Africa Confidential and the Financial Times. He has been a Reuters Fellow and his fiction has twice been shortlisted for the Caine Prize for African Writing.

This text features in the latest Chronic Books, the review supplement to the Chronic. This edition of Chronic Books explores radical comics from 1970s South Africa, Nigeria and India as well as a range of dispatches, interviews and reviews.