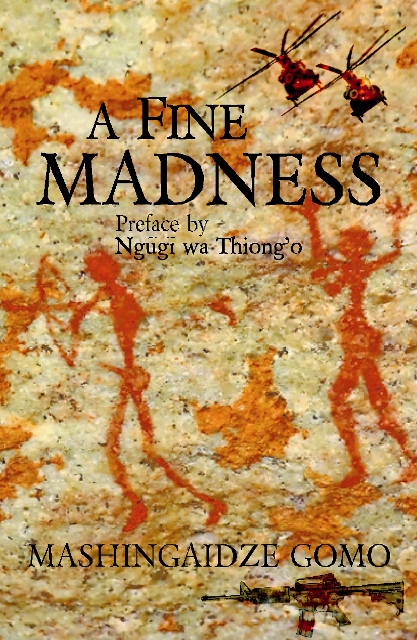

The African soldier is portrayed in the mass media as a terrorist zombie, trained in the service of power-hungry despots and inclined to rape women and children. Mashingaidze Gomo, who served in the Zimbabwean Air Force during the war in the Democratic Republic of Congo, puts another face to the name in his novel, A Fine Madness, forthcoming from Ayeba Clarke Publishing. The Chronic publishes an excerpt this week, with the following introduction as penned by the author.

A Fine Madness

Mashingaidze Gomo

Ayebia Clarke (2010)

Some friends have expressed surprise at the idea of a soldier taking time to write a novel, but I wanted, through a selection from war diaries and other personal documents, to give the African soldier a more human face, with the recognisable fallibilities of the everyday person, right down to the simple joy of weeing. I wanted to show the African soldier as an ordinary man who desperately misses his lover, a man whose name is a record of colonial history and, above all, a man who has studied the concepts for which he fights.

The surprise expressed at my taking time to write indicates to me that to many people, the art world and the military are mutually exclusive. Yet deep inside, I feel the military experience made me a better artist. I have always felt that art is for those who feel very deeply about issues. I am sure that is what makes art created in contexts of tragedy so powerful. Such art cannot be ‘cool’ when it is itself a site of struggle.

I wrote A Fine Madness from the position that art is a contest in which the artist is the combatant who must identify, intercept and deconstruct hostile meanings and self-destructive complexes in order to reconstruct dignity and a meaningful vision that is sympathetic to African interests. In the DRC, at times, I thought that task was almost insurmountable.

When my friend Judith Mupanduki typed the manuscript she observed that parts of the text read like poetry and she typed them as free verse. When she was done I refined the entire text along those lines. I thought that the poetic disorderliness was in keeping with the context in which it had been created, because war is disorderly.

Paradoxically, poetry also came across as neat and I felt it was the appropriate smart weapon for making war on neo-colonial positions because it has very few loose ends. I perceived the poet as a minimalist, who in a military analogy would be the commando, or light infantry, wanting to account for every round. In the same manner that an armourer packs an incendiary shell with high explosive for a devastating effect, I found that I could pack a high density of meaning into very few words.

Poetry allowed me to replicate physical battle into a metaphoric one. It could be fired at a hostile notion like a machine gun, with the repetitive syntactic inversion of the conjunction “and” serving to sustain the rattle of reason. And then, one could convert it into a sniper’s long range rifle, complete with the telescopic sights of history to deliberately knock out stubborn ideological strongholds. And, some targets, like democracy, rule of law and religion needed to be stripped of all deceptive euphemism before assault, and that called for the prose to come in as an artillery barrage that tramples on a mass target all night long before a dawn ground attack.

Throughout my creation of Madness, I also found mbira music very inspirational. Even though it is music I have known all my life, in the DRC it assumed heightened meaning. It was the only weapon I ever carried that was strictly African. On the eastern front, a gunner from the commando carried an mbira set which we used to play through the nights and the music made us wretchedly homesick. The music became a signal of contact with the past, thus putting us and our actions into a historical context that kept the past alive and the present in memory.

Rearguard Action

And the Alouettes beat on

Two birds of war, on the trail of a tireless horizon

Running, running and running in an hour that was as

long as an afternoon

And sometimes the horizon would hang around a column

of rain, as if for a chat, only to abandon it on our approach

And sometimes the horizon would diffuse into a shower

of rain…a smoke screen that accorded the horizon

moments of respite and time to pill dirty tricks

unobserved

And we would beat into the soft showers, visibility

reducing to zero and the horizon would not be there

And the mistyrain would keep us anxious company for

moments longer than necessary…

Fighting a stubborn rearguard action for the horizon…

A celestial guerillaterrorist, deterring our progress and

Giving the horizon time to pull away

And we beat on…over uncharted territory

We beat on…westward, informed by a global

positioning system, divining directions to places lost in

the jungles of the planet

We beat on, led by the high-tech angel of mercy clamped to

The pilot’s stick and rising to the occasion inspired by a

hi-tech eye in the sky…a satellite that scanned

heaven and earth, playing God, knowing every place

there is on the planet, giving consultation to whoever

cared to consult and leading anybody anywhere

And at last, we came to city yaBokungu

And the townfolk came to watch the landing

And the MI crews too

And the commandos who had left Boende ahead of us

And the commander, a lieutenant colonel, said, ‘Had you

decided not to come?’

And the pilots said, ‘No sir. We were on our way.’

And it felt good to be together again

And we were allocated the same accommodation with the

MI crews…a war-broken house on the edge of the

Jungle

And we were then taken on a tour of town

This story, and others, features in Chronic Books, the review of books supplement to Chimurenga 16 – The Chimurenga Chronicle (October 2011), a speculative, future-forward newspaper that travels back in time to re-imagine the present. In this issue, through fiction, essays, interviews, poetry, photography and art, contributors examine and redefine rigid notions of essential knowledge.

To purchase in print or as a PDF, head to our online shop.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work.