by Kwanele Sosibo

Photographs by Lehlohonolo Moeketsi

18 March, Atteridgeville

“Sort these people out, we also don’t want them here.” The words were uttered with such bureaucratic efficiency that no eye contact was required as the policemen climbed into the van, satisfied that their instructions would be carried out swiftly.

Tuesday 18 March was turning out to be a particularly bloody day. Earlier that morning, around 11am, a swelling crowd of people, apparently from Phomolong, was canvassing support for a march around services to the police station in Siyahlala and Brazzaville. The age old issues, they said: electricity and housing.

People were practically being forced out of their houses to join the march. Moses Mhlanga, a Mozambican businessman with shops in Siyahlala and neighbouring Brazzaville, was among those being “set up”. The strategy was simple enough: play on their loyalty by forcing them to join the march, re-route and attack.

When the marchers reached the police station, where they were due to meet the mayor, they were informed that their gathering was illegal. In the confusion that ensued, word got out that people were heading back to Brazzaville to take whatever belonged to “outsiders”.

Hearing about this proposed plan, Mhlanga called out to one of the policemen, asking him if he had just heard what people in the crowd were saying. “He said to me: ‘Bru, we can’t be in two places at once.’”

Knowing exactly what that meant, Mhlanga and the other “outsiders”, a motley group of shop owners and residents, scrambled back to their bases for a last ditch attempt to save their livelihoods. In Siyahlala, Mhlanga and a couple of his workers tried to form a human wall around his spaza shop, but the torrent of stones, kicks and fists proved their undoing. In a flash, around R125,000 in stock had been looted and R6,000 in cash had gone missing before they burnt the shop to the ground. At the same time, his Brazzaville operation also went up in flames.

“Before this whole thing,” remembered Mhlanga, “Jeff [Ramohlale] had called a meeting where he said to us: ‘Do you know about what is happening in Rosslyn [near Soshanguve]? I can tell you now that this thing is coming here. Now I can stop this thing, but you are going to have to pay me to do it.’

“I said to them: ‘If you want to loot our businesses, you can loot them. I am not going to pay you or anybody.’

“They wanted, in total, R3,900 from us. That meant R150 from each person. So in total, there must have been about 26 people whose shops got vandalised. The funny thing though, was that even those who had paid had their businesses vandalised. The only guy who got away free was a Mozambican businessman we know as Sithole. That’s because he was vocally advocating that we all pay.”

After a night in hospital, Mhlanga spent the next four days in Tsunami, Brazzaville with his girlfriend. Soon, she was being asked: “Liphi leligrigamba olifihle endlini yakho?” (Where is this foreigner you are hiding in your house?). He knew then that he had to leave.

Down the hill from Mhlanga’s Siyahlala shop, another four-man wall was collapsing under relentless beating and a torrent of abuse. Eventually the owner, Thomas Moyana, told the men to take whatever they wanted. One retorted that they didn’t need his permission. Ma Elie Dluwayo, Moyana’s assistant, let go of Moyana’s hand and stood up very slowly. Moyana remained kneeling, on all fours like he was about to spit his teeth out.

Johannes Mothise tried to help him up while James Ndobe, the tallest of the men, held on to a pillar and bloodied it, studying the mayhem as if etching the looters’ faces in his memory. He counted about nine men taking away what they could with hands already carrying weapons. The last one to get out of the shop poured petrol over the remaining stock and used matches from inside the store to set it alight. Moyana got up in time to see his shop burn.

How he had ended up in Nelspruit thereafter, was a blur. He didn’t even remember being stitched or bandaged.

16 May, Nelspruit

Moyana had to remind himself where he was each morning. He couldn’t go on like this for much longer. He, along with several Mozambican shopkeepers, had barely survived the lynching of two months ago.

It was Sunday. It was as if he could tell by the way the light fell on everything, even here in Kwanyamazane – closer to home but further away from himself.

Usually, on Sundays in Atteridgeville, when he still had the shop in Siyahlala, he liked to listen to the radio with Ma Elie. If he was home, or at least what he had thought home was for a while, he would turn on Thobela FM. He always found the interpretations of the Sunday sermon quite fascinating as a study in linguistics. The sePedi preacher would go first, followed by a siShangane interpretation. SePedi was the more guttural of the two languages, siShangane the more musical, lightfooted even, as if in preparation for a retreat.

But he wasn’t home and he hadn’t got the hang of Ligwalagwala. SiSwati was a bit too seductive for him, even in matters of gravity.

A slight chill was starting to set in even in subtropical KwaNyamazane. He felt discomfort, despite the closer proximity to Mozambique. It was the metal bed. His feet were hanging over its steel frame, bending his Achille’s tendons. His weight was straining against the springs. No wonder the nightmares. He didn’t consider them as such though. The worst one was over, he thought.

He thought about the radio again. Was he dreaming last night? A sexy female voice had said something about the violence spreading to Johannesburg before he cut her off, drained. Then again he had slept late, thinking about returning to his business, leaving his younger brother, Eduardo, to his.

“Uzwile bathini TMan iyaqhubeka lento.” (Did you hear TMan, this thing is picking up steam.) Eddie could be cryptic sometimes. He hadn’t even heard him come in, but this time he knew exactly what he was on about.

He turned the radio on. The news had passed, but the camp voice of a male show host was talking about Jeppestown, people running in the streets, barricading flats, scurrying into police stations like thugs fearing mob justice. In Jozi, of all places. What could have sparked it? He wondered if there was some southwards trajectory to all this. First Pretoria, then Alex, then Diepsloot, Thembisa, now Jo’burg. “Will we all be washed out to sea?”

He could make out three pairs of feet now in the four-roomed shack. He tensed up a bit. Since 18 March, two months ago to the day, in fact, he had avoided sleeping on his right rib. He had been kicked by a steel reinforced boot, repeatedly, while he tried to protect his bleeding head. He had learned some lessons he hoped never to use again that day.

First, when being assaulted with rocks, the quicker you prostate yourself, the better. Your will to look your opponent in the eye is drastically reduced by the danger and, in turn, his will to inflict more damage is decreased. He didn’t even like Ghandi, he thought.

Remembering why he was in KwaNyamazane, he felt safe, as safe as an alien could be. He turned the radio off in time.

“Uzwile uMoses ubuyele?” (Did you hear Moses went back?). Everything with Eddie came out like a challenge.

“Ya. For two weeks manje (now)!”

“Manje wena (And you)?” he asked, opening the door.

He didn’t answer that one.

When Eddie quit high school against his mother’s wishes, Moses Mhlanga’s house in Hammanskraal was the first place he had visited. Mhlanga did his trading thing, he fixed cars and upholstered anything you dared him too. That was nine years ago. He still looked up to Mhlanga. Everyone did.

Mhlanga hated relying on people; he would rather they rely on him. Having lived in South Africa for 27 years – five of those as a citizen – he knew that was Survivor South Africa rule number one. But here he was in Phomolong, on May 16, with his uncle, Ngwenya, glued to the TV, trying to figure out what was unfolding.

The two-roomed shack was now being shared by Ngwenya, himself and his two workers. It was nothing like the palatial six-roomed “mansion” he occupied with seven kids, two wives and four workers before his life was turned upside down. In the past two months, Mhlanga spent the first six weeks coming in and out of Atteridgeville from his base in Winterveld (where, ironically, the violence started), not too far from Soshanguve, where Ngwenya had first sheltered him.

He’d been settled for about two weeks already.

“People like to ask me if I am scared,” Mhlanga said when asked about it now. “But what is the use of being scared. I have no money, no clothes, my children have no food. I had children here, you know.”

After the flare up, Mhlanga sent one of his wives to Thembisa and the other to Jo’burg. Top of his agenda was to get his two businesses – one in Brazzaville and the other in Siyahlala – back on the ground. They were both named Thandabantu, which was an accurate reflection of his nature.

Not a fan of Sundays (“because business is always slow”), he noticed something funny in the atmosphere. Bands of kids were having spontaneous meetings on the streets, as if recruiting for a march, again. One of the young workers went out to investigate. True enough, there was excitement about the violence on the East Rand and in Johannesburg.

“Bathi siyabaphinda, akusikho Egoli kuphela.” (They say they will come for us again right here, not only in Jo’burg.)

“Bayagula!” (They’re mad!) exclaimed Mhlanga, more irritated than scared. But deep down he was worried. Rebuilding would not be easy, especially because he was his own man.

At some point that Sunday, Mhlanga and Ngwenya made the decision to join the giddy march. He had to play his enemies close. In fact he had to play them close enough for them not to see it. The smart thing was to stand toward the back.

The idea was to march to the RDP houses, and then back to the taxi rank on the way to the police station. The march got stopped halfway by a heavy police presence. By midnight, Mhlanga was in bed, sleeping peacefully.

Jeffsville

Earlier that day, in Jeffsville, an unlikely king assumed an unlikely throne. Jeffrey Ramohlale’s lumpy body was a tight squeeze on his fold-up, green and white camp chair. Hiking sandals crossed his feet, while shorts and a dress shirt covered his stumpy physique. The scars on his face suggested that he was the survivor of many a war, but he was not in the mood for trading war stories today.

Jeff’s liquor business usually does a roaring trade, but the men surrounding him in a perpetual human-high wall seemed to have no time for the drinks they were casually sipping, or fluid conversation for that matter. They passed the time by staring at Jeff or playing cards.

A youth came to buy some booze and asked Jeff if he was aware of today’s plan of action.

“What action? Bayekeleni labantu ngoba masebehambile futhi nizobakhalela.” (Just leave these people alone because when they are gone, you will complain again.)

“This thing is all over man. All over. So how can people say it’s me. If people are fed up because of houses or electricity or whatever, who do you think they will take it out on?” he asked rhetorically, almost apologising for the youth’s callousness.

It was a strange sight, the man accused of killing foreigners surrounded by Mozambicans. It’s hard to blame the violence on Jeff, despite the fact that half of Atteridgeville seems to think of him as prime evil. Personal fiefdoms are the capitals of alternative realities, I discovered. In his element, he exuded a charisma beyond description, to such an extent that everything he uttered became simultaneously true and false.

“You can ask all of these people, they will tell you that I brought them here. So how can I be responsible for this xenophobia?”

To understand how Jeff gained his mythical aura, one has to engage in a bit of time travel, to the early 1990s.

Jeff was born in Lady Selborne, near Magaliesburg in 1948. He quit school in Grade 8 and at 24, joined the ANC, under the guise of Atteridgeville, Saulsville Residents Organisation (Asro). While living in Atteridgeville, he became an organiser and deputy chairperson of Asro and, as he put it, “chief problem solver”. This is how people came to rely on him.

It’s unclear why Jeff decided to establish his own settlement, but he maintained that he was “tired of solving problems and just wanted his own place”.

He was also cagey about why he would move with 300 people, except to say that problems escalated and became “unmanageable”.

In 1991, he settled in Lotus Gardens, with about 300 people and they were promptly removed to another spot, near Iscor in Pretoria. This time, Jeff claimed he was offered R500,000 to dissolve the settlement of shacks, tarpaulin and plastic shelters. He reached a compromise, moving his entire entourage to the present-day Jeffsville. “The people named it Jeffsville because they say I started everything here.”

Jeff said that although it was mostly South Africans, a lot of Mozambicans joined in early on.

In Jeff’s opinion, the tensions in this area, mostly around housing, would be quite easy to resolve: “We drew the city council a map because they didn’t have a solution. There are areas that can be developed here, but you must move people that have applied for housing in blocks. We are tired of people from Hammanskraal and Garankuwa getting houses here. That’s why there is a ‘tsotsi element’. If you take two people from Jeffsville, two people from Phomolong, how are you going to see that you have moved people?”

Ever the problem solver, Jeff had another map, one that absolved him of blame as chief instigator and recast him as a peace broker.

“In South Africa, this thing started in Winterveld in the North West. From Winterveld it went [south-eastwards] to Soshanguve. From Soshanguve, [north-eastwards] to Hammanskraal. From Hammanskraal [southwards] to Mamelodi. From Mamelodi [westwards] to here in Itireleng. From Itireleng, there was a meeting there in block K in Jeffsville.”

Although he didn’t disclose the explicit contents of the meeting, it was quite clear that the call to destroy property came out of it.

“The day of the march (18 March), they got the chance now to attack, when people were at this service delivery gathering. But the foreigners will tell you that I bring them back. Nobody takes anybody’s job. The majority of South Africans are lazy,” said Jeff, all diplomacy escaping him. “We can go outside here where people are selling vegetables, the majority of them are Mozambicans and Zimbabweans. These women, what they know is to play cards with the money from the grants.

“People that don’t like those foreigners, that believe they must go home, I always tell them that they are not the government. The government is the one who must take them back home. Not us. If somebody has an ID, why must I chase them away because he has an ID.”

As Jeff’s own brand of magic would have it, the government was listening. But everything about its response to the plight of Atteridgeville’s vilified suggested contempt for human dignity.

Soon after March’s outbreaks, Mangena Mokone Primary School, closed for school holidays, was turned into what was billed as a refugee camp. The reality bore all the hallmarks of a deportation trap. Tafadza Chidodo, 27, a handyman from Zimbabwe, said immigration officials confiscated asylum papers earlier in the week of 24 March and sent more than 60 refugees to Lindela (the infamous holding centre north of Johannesburg), where they awaited deportation.

“Some of them [immigration officers] are telling us to go home and vote, but what about the Malawians?” he asked.

Home Affairs was unrepentant, with spokesperson Cleo Mosana saying: “Not to take action against illegals would be setting a bad precedent.”

Along with quiet diplomacy, this seemed to be the most robust display of South African ‘foreign’ policy. Let them come, but we will use any opportunity to remind them they don’t belong here.

At least six people lost their lives in Atteridgeville’s pre-emptive attacks: two were Zimbabweans who were beaten and then set alight in Brazzaville. More than 25 businesses were destroyed and more than 50 people were injured. Given the collusion of the state, police and com-tsotsis, the message, as shopowner Moyana put it, was clear: “When Mandela goes, you will never set foot here again. This was just a warm up.”

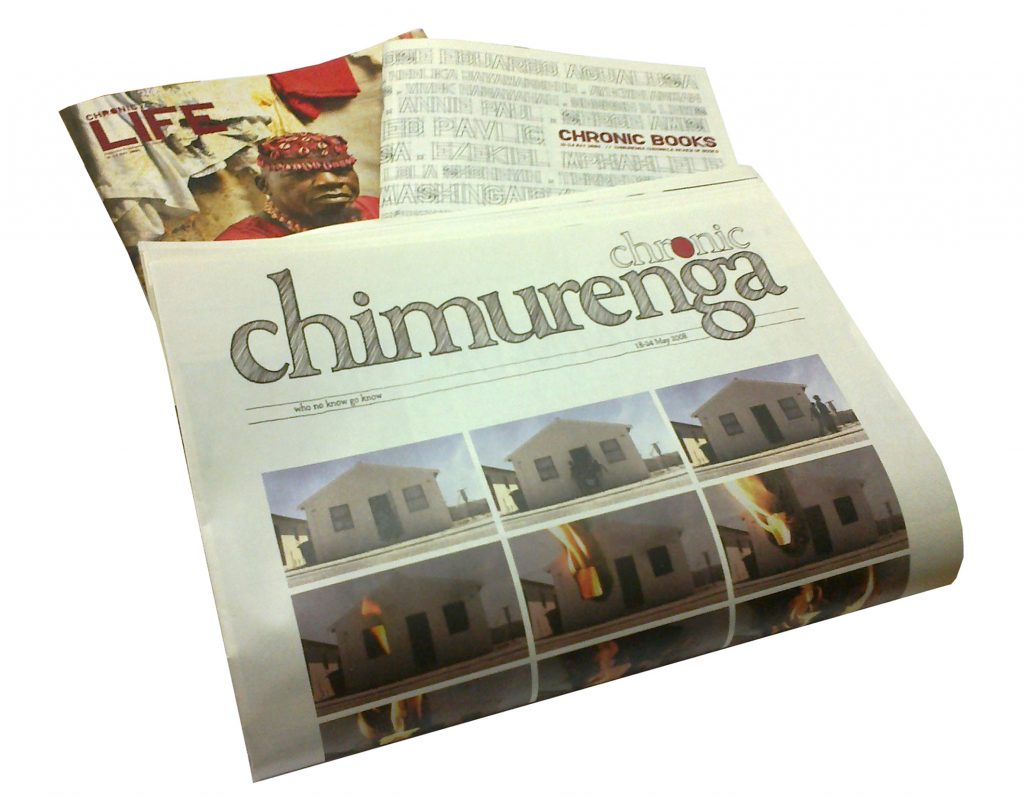

In commemoration of our 20th year, we will be digging through our extensive archive.

This story, and others, features in The Chimurenga Chronicle, a once-off edition of an imaginary newspaper which is also issue 16 of Chimurenga Magazine. Set in the week 18-24 May 2008, the Chronic imagines the newspaper as producer of time – a time-machine.

To purchase as a PDF, head to our online shop.