By Stacy Hardy.

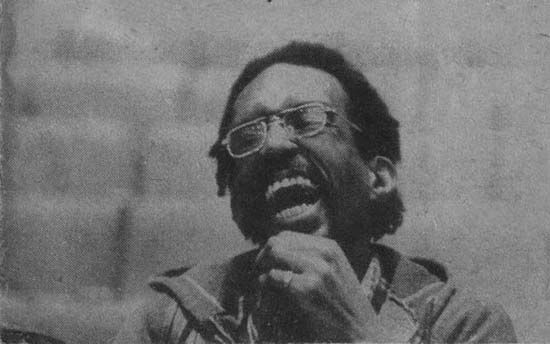

Julius Eastman had a way of walking. He had a swagger, a way of swinging hips. He rarely strolled or ran. Instead, skin tight jeans/ black leathers slung low on his waist, sucked down by the velocity of his gait, he cruised and rolled. He played loose. He played cool. He worked fast.

He scored Stay on It in one sitting. He wrote through the night, the full next day, the next night. He wrote fast. He wrote moment, place. He wrote sentiment and soul. He orchestrated the body: his body, body in motion, body as it flexes to move a pen, form a fist, make mark, lift a drink.

He rewrote the classical music canon. He inserted pop. He noted free improvisation. He bucked the conventions. He fucked minimalism. He reworked the rulebook: Cage’s anal atonal progressions, Glass’ linear additive processes, Reich’s phasing and block additive methods. He started the Post Minimalist revolution, New Music, Improvisation, call it whatever you like.

He made the call. He beat them all to it: John Cage, Steve Reich, Philip Glass. This was 1973. This was America. Glass was still only glistening on the surface. Reich was outside the country, hauled up somewhere in Africa, playing poacher, plundering Ghanaian polyrhythmic beats. Cage was still stuck in his cage, his soundproof room, his anechoic chamber. Cage was still tuning silence; tuning into his nervous system in operation, low throb of his blood in circulation. Cage was tuning: “Until we die there will be sounds.”

Who needs them? Eastman was already at the edge. While Cage could only hear his body, Eastman’s music mapped those sounds: pulses pounding, sweat producing, blood surging in veins. While Reich filched, Eastman felched, digging his tongue deep, exposing himself, getting off on his own shit. Fuck the division between private and public, feral cruise and cocktail soirée. Fuck stuffy formalism of avant-garde composition: “forms”, “malls”, “isms” and restrictions.

“He had radar that could detect bullshit.” He hated that shit. He hated hip hyp-o-crazy: the lecture halls, the concert chamber; the sound proofed rooms and white gallery cubes. Everything purged of colour. Specifically: all the walls and the ceilings and the floors; white. More white than white, the kind of white that repels. No smells, no noise, no colour; no doubt and no dirt. No nothing. No eating, no drinking, no pissing, no shitting, no sucking, no fucking.

He rebelled. He headed out. He hit the gay clubs, the crack houses, disco dens. He listened up to the sound on the street. He saw the violence. He saw the hate. He saw anger. It moved him. It ran him. It called his shots. He stayed cool with it. He stayed justified. He channelled the rage. He wrote it down. He stayed on It; He spread the word. He said: “Find presented a work of art, in your name, full of honour, integrity, and boundless courage.”

It was futile. They ignored him. They indulged him. They used him. They strung him along. A black face looked good on record. 1974. The Creative Associates on the bench of the Albright-Knox Gallery. Official photograph. Used by permission. Front, l-r: Julius Eastman. His features a blur, the white balance thrown out – shooting for white – just a duffle coat and sneakers, just an outline, a black smudge, a dark mark, stop gap framed by smiling white faces.

They used him to fill the gaps. Petr Kotik looked him up. He was putting together a concert series. Big names: John Cage, Earle Brown, and Christian Wolff, the original New York School. They wanted to diversify. They were looking for someone to represent. Kotik wooed him. Kotik went through the motions. Kotik invited him around. Uptown apartment. Konik at the door. He said, “Come in. Straight through here.” He pointed with his hand. He led the way. He said, “Grab a seat.” Eastman sat. Eastman stared. Fancy pad: white walls, plants and lights, stiff long-back chair. Konik poured drinks. Konik smiled. Konik paid lip service. “What kind of music do you want to hear? You hungry?”

He said, “Big Break.” He said, “Big names: John Cage, Earle Brown, Christian Wolff.” Eastman sat, stared. Eastman listened. Eastman timed the pause. He felt the hate. He felt the anger. He started to say – No, wait. Maybe? He took a breath. He challenged the rage. He counted notes. He took the score. He said, “Sure Pete!” He sat. He smiled. He had this craaazy idea.

The performance took place. 1975. The June in Buffalo Festival, SUNY Buffalo. Now legendary. Now infamous. Kyle Gale told and retold the story: “Chaotic at best! Eastman performed the segment of Cage’s Songbooks that was merely the instruction, ‘Give a lecture.’ Never shy about his gayness, Eastman lectured on sex, with a young man and woman as volunteers. He undressed the young man onstage, and attempted to undress the woman…”

He started with her top button. He worked fast. He worked fastidiously. His hands jumped. He dripped sweat. Second button, third. She wasn’t sure. She trembled. She shut her eyes. Fourth button. The audience twittered. The audience buzzed. She looked up. She made eye contact. Her eyes swam. She grabbed his hand. Everything froze. Time hung back. She looked down. She broke free. The audiences erupted. The audience roared. Someone stormed the stage. Someone hit the lights.

All hell broke loose. John Cage freaked. Cage raged. Was that meant to be a joke? Who’s laughing? Am I laughing? He came down hard. He came down spitting words, throwing authority. He said, “I’m tired of people who think that they can do whatever they want with my music!” He stormed. He banged the piano with his fist.

He said, “The freedom in my music does not mean the freedom to be irresponsible!” He used his lecture’s voice. He couldn’t make the break. For all his talk about crossing boundaries – noise/ music, life/ art – he couldn’t take the leap. His “anti-art” was still the same old shit: natural law devalued, social tradition minimized, rebellious gestures only accepted if they stayed safely walled in, caged within the tradition they sought to denied. Cage as cage.

Even his thinking on silence was caged, locked within the audible order, a lecturer’s voice: something to learn, rather than lose yourself in. Silence as ambient sound, nonintended sound. Silence as the sounds of life. He said, “Until we die there will be sounds.” He said there will only be silence in death. The implication was left hanging: we can’t experience our own death so we can’t experience silence. Silence, like death was the impossible crossing of a border. Audibility vs. inaudibility, life vs. death: oppositions that can’t be overcome, borders that can’t be crossed. And the hierarchy was clear: Life was where it was at. Death was the undesirable, a dispensable deviation, something to be silenced.

Cage said, “I have nothing to say and I am saying it.” Eastman had something to say and he was unsaying it. Cage raged and lectured. Eastman acted. He showed up the con of Cage’s “instructions”. He de-con-structed. He gave voice to silence. He injected real life, lived experiences, street politics into art. He created an unsound politico-musical discourse, a line of flight that radically threatened Cage’s abstract political discourse, the white language of the classical avant-garde. He scared the shit out of Cage.

Cage reacted. Cage hit back. He said, “Irresponsible!” He rallied support. Walter Zimmermann called it “rotten”. Peter Gena said, “Abuse!” Petr Kotik called it “sabotage”. He said, “I should have guessed he was unsuitable.” He said, “scandal.” Eastman was tagged: Crazy Nigger. The reputation stuck. The blacklist built: Eastman the Evil Nigger, Eastman the Savant Saboteur, Gay Guerrilla sooo-preme.

His guitarist brother Gerry said, “Give it up Julius. Play jazz. At least a black man can make half a living playing jazz.” Fuck that shit, man. He refused. He knew the score; their story is history: crazy black gay mutherfucker, all danger and despair and downward trajectory. Ismael Reed’s old “post-Mailer syndrome”, the “Wallflower Order”: “Jes Grew, the Something or Other that led Charlie Parker to scale the Everests of the Chord… manic in the artist who would rather do glossolalia than be neat clean or lucid.”

He refused to be composed. He answered them with If You’re So Smart, Why Aren’t You Rich? A 20-minute fuck you. Fuck you to your score. Your over-determined definitions of what it means to be black. Pre-de-scribed borders and hierarchies: beginning/end, classical/jazz, silence/sound, hite/black, between order/ disorder, meaning and meaninglessness, life and death.

He worked on unweaving the whiteness from within. He started at the end, a funeral march, a single line, chromatic scales on slow ascent, going going then BAM! Drawing it up, drawing it out, ripping it open, a quickdraw halt, a slash, a silence, coma, full stop, semicolon connoting rhythm of speech, interrupted thought. Then more scales, building slowing, coalescing, multiplying the metre into a seething swarm, a glowing brass mass where desire equals death, where death, and the approach to human death, is no longer an end but a beginning.

He kept his own score. He rocked up for rehearsals dressed like a jazz cat, a disco queen. All black leather and chains and dripping desire and fuck yous. He pitched high or drunk. He hung loose, he jived, whisky slung low in left hand, a tight fist. Then he hit the piano and everything changed. Time changed. Time redacted. Space erased. Knuckles became fluid, joints broken down, fingertips riding hard and wide; trembling then going taut.

The contradiction was too much. They wrote him out. They wrote him off. They accused him of silencing himself. “He could have had it so good if only he hadn’t had the personality problems.” He lost his post at SUNY-Buffalo. They called him in. The office. Two chairs. One desk. The books lining the walls like ghosts from another epoch. The Professor shuffled papers. His button down shirt perfect white, white on white. He cleared throat. He glanced up. He said, “Take a seat”. He cited, “Neglect of administrative duties.” Eastman didn’t stay for the rest. He walked. He took the stairs. He said, Paperwork? Fucking paperwork? He didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. Outside it was warm. Thirty degrees at noon. Campus was crammed. Students between lectures, taking lunch. They jostled him. They pushed past.

He kept walking. He followed the sound on the street. Downtown, 1980, music pumped from open windows and revved motors, fragments and samples, notes and the repetitions. Richard Pryor’s world of “junkies and winos, pool hustlers and prostitutes, women and family” all screaming to be heard.

He wrote hard and fast. He scored Evil Nigger, Gay Guerrilla, Crazy Nigger in close succession. He tore into classical tropes and constructs. He deconstructed. He found rhythm. Street politics embedded in the beat, the repeated piano riffs, the propulsive badbadDUMbadaDUM brass blasts. Cool cadence balanced rhythmic flow, as in poetry, as in the measured beat of movement, as in dancing, as in the rising and falling of music, of the inflections of a voice, modulations and progressions of chords, moving, moving through a point beyond sight, sound, vision, being.

He played the preacher man, rocking out on a counting-in chant, “one-two-three-four”. He played the poet. He re-dubbed Lee Perry’s “I am the Upsetter. I am what I am, and I am he that I am”. He wrote The Holy Presence of Joan of Arc. He said, “This one is to those who think they can destroy liberators by acts of treachery, malice and murder.” He rapped Richard Pryor’s Supernigger. He was unstoppable.

He played The Kitchen. He hit the stage alongside Merdith Monk and Peter Gordon. He hooked up with Arthur Russell. He toured Europe. He filled houses. He flew off. He came back. He put out feelers to record. He was ready to get it down. To get it out. Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians was going massive. Glass’ Metamorphosis was everywhere. He contacted cats he knew via the circuit. He said, “What’ve you got going?” He waited. He made more calls. He chain smoked and watched TV. He slept through whole days. He woke. He drunk whisky. He slept. He watched TV. Old Pryor skits on NBC. “White. Black. Coloured. Redneck. Jungle bunny. Honky! Spade! Honky honky! Nigger! Dead honky. Dead nigger.”

He played the college circuit just to keep going. North Western 1980. Members of the faculty took offence. The African American fraternity didn’t like the nigger shit. It was like Édouard Glissant never existed. Like Ismael Reed, Richard Pryor, hip-hop never happened. No word on the street. He had to explain. From the beginning. “Recontextualization? You know the whole ‘re-appropriation’, ‘recannibalisation’ thing?”

He took to the mic. He said: “There are three pieces on the programme. The first is called Evil Nigger and the second is called Gay Guerrilla and the third is called Crazy Nigger.” He spoke smooth. He flowed easy. He mirrored Pryor’s buzz in making obscenities sing. He paused after each title. He let it hang. He waited for it: the reaction, breath suspended, waiting for a ripple, a laugh, some kind of recognition of the humour at play. Nothing. Fuck. His audience was silent. Not even a twitter, a nervous giggle. He held the pause a second longer – Jesus, even he felt like laughing – but no, nothing. Just silence, just Eastman, just his nerves’ systematic operation, his blood’s endless circulation.

He tried again. His voice wavered. His voice woofered. It bounced high and wide. FUCK – Overfeed. Overamp. From the start. He said, “Nigger is that person or thing that attains to a basicness or a fundamentalness, and eschews that which is superficial, or, could we say, elegant.” He said, “There are 99 names of Allah.” He paused. He said, “There are 52 niggers.” But still it wouldn’t go away. The whiteness always returned, whiteness woven into the fabric of Culture, whiteness locking everything else out. Silent. White faces stared back. Blank, unmoved: they could see only one.

One more drink. One more pill. It was getting tight. 1982. Nothing coming. The walls closed in. Cash was low. The apartment cost. The clubs cost. The drink cost. He got headaches. He drank himself to sleep. He swallowed whisky shooters. He popped uppers. He shot poppers. A downhill slide. Cornell University turned him down. “He was just too damn outrageous.”

A failed application to the Paris Conservatoire. The letter came in the post. One white envelope, black type. He said, “Damn them damn them damn them.” He tore it up. He let it drop. He headed out to score. He head east, the lower Eastside. Further out, the windows all covered meshed-over glass burglar proof stuff; homeboys on the sidewalks rhyming beefs, little men with big shirts and the chicks in tight skirts.

He kept going. He walked. He didn’t give a shit. He felt zero. He felt zip. He felt ate up. His skin buzzed. He took a left. He crunched glass underfoot. He took a right. Low door. Dark interior. Match boxes and glass pipes. Cracker jacks on low stools. White smoke that hung in low clouds. He took a seat. He took the hit. He sucked deep. He held it in. He let go. He felt it hit. His mouth closed. His head dropped black. His eyes rolled. And white appeared. Absolute white. White beyond all whiteness.

White of the coming of white. White without compromise, through exclusion, through total eradication of non-white. Insane, enraged white, screaming with whiteness. Fanatical, furious, riddling the victim. Horrible electric white, implacable, murderous. White in bursts of white. God of “white.” No, not a god, a howler monkey. The end of white.

[Julius Eastman died in 1990. Unjust Malaise, a 3 set CD of his compositions, culled from university archives, was released by New World Records in 2005. This was Eastman’s first official release. No commercial recordings of his work were made during his lifetime.]

Stacy Hardy is a writer living in Cape Town. This essay is also available in print as a Chimurenganyana and in Chimurenga 11: Conversations with Poets Who Refuse to Speak (2007).