The editorial in the first issue of The Cricket spells out the publication’s inspiration: “The true voices of Black Liberation have been the Black musicians .” Subtitled Black Music in Evolution Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones), Larry Neal, and AB Spellman in 1968 in the spirit of the hip, improvised come-to-consciousness of Black Nationalism, using the perspective of the music being created within it.

The Cricket took its title from a music gossip of the New Orleans cornet master Buddy Bolden. Like it’s namesake it was defiantly street level. Within its visually ascetic, mimeographed pages, it resonated with the same aura of revolutionary spirit, city street authenticity, and interartistic collaboration that defined the Black Arts Movement of Harlem in the 1960s.

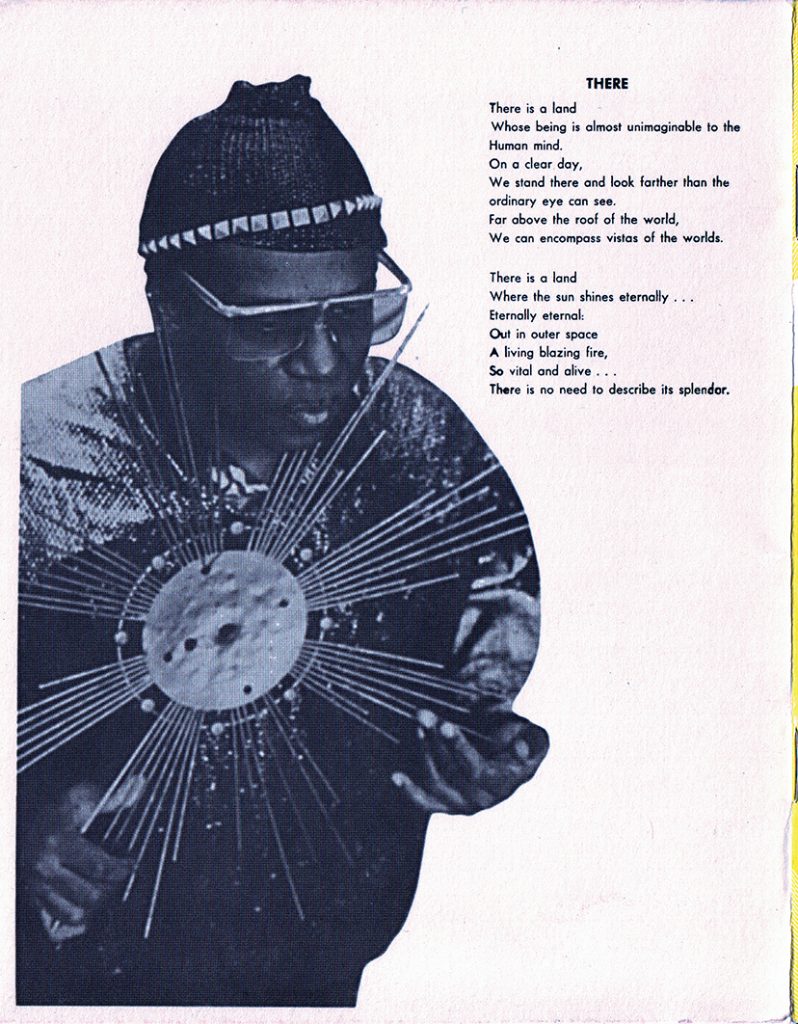

Just consider the names, the conjurer all-star syllables of a revolutionary moment in history: Sun Ra, Milford Graves, Sonia Sanchez, James T. Stewart, Don L. Lee, Clyde Halisi, Stanley Crouch, Cecil Taylor, Mwanafunzi Katibu, Albert Ayler, Willie Kgositile, Aaron Ibn Pori Pitts, Archie Shepp, Stevie Wonder, Ornette Coleman and more – and all that in just four issues published over only two years.

The cricket jittery graphic design matched its eclectic content. Within its bright covers, the world of black culture was explored, interrogated, celebrated, exploded. A music magazine? Sort of. A literary magazine? That too. A critical journal. Safe. A philosophical intervention into everyday life? Absolutely.

The Cricket of the Energy of Various Musicians: Sun Ra, the percussionist Milford Graves, and the pianist Cecil Taylor are listed as advisors. Poetry and drama intermingled with record and Black Nationalist polemic. Musician-writer-activists spun verse and prose; poet-essayists tried to capture the pulse and attitude of the new music while trumpeting black power and condemning white racism. Stylistically, their words in all forms embodied a kind of verbal jazz. “We wanted an art that was as black as our music,” Baraka recalled. “A blues poetry (Langston and Sterling); a jazz poetry; A funky verse full of exploding antiracist weapons and new music poetry that would scream and taunt and rhythm-attack the enemy into submission. “

After four issues however, The Cricket was destroyed by the political agenda and embodied. As Baraka later reflected, “We had gotten so deeply into the political aspect of it [Black Nationalism] that the Cricket were let slip …” While numerous publications from Ron Welburn’s The Grackle (mid-1970s) to Straight No Chaser (1988 -) The Cricket ‘s Spirit, no one has yet matched its innovation, creative promiscuity and intense belief in the possibility of freedom. As Baraka says, “Beauty has nothing to do with it, but it is!”

traduction française par Maymoena Hallett

L’éditorial du premier numéro de The Cricket précise l’inspiration de la publication: “Les voix véritables de la Libération Noire ont été les musiciens noirs. Ils furent les premiers à se libérer des concepts et sensibilités de l’oppresseur.” Avec pour sous-titre Black Music in Evolution, le magazine fût crée par Amiri Baraka (û l’époque LeRoi Jones), Larry Neal, et A. B. Spellman en 1968 dans l’esprit branché, prise-de-conscience improvisée du Black Nationalism, utilisant pour base la perspective que la musique est crée au sein de celle-ci.

The Cricket prit son titre d’un journal de potins musicaux imprimé au tournant du siècle par le maestro du cornet de la Nouvelle Orléans, Buddy Bolden. Tout comme son homonyme, son niveau était, avec audace, de rue. Sur ses pages visuellement ascétiques et miméographiées, résonnait la même aura d’esprit révolutionnaire, d’authenticité des rues urbaines, de collaboration interartistique qui définissait le Black Arts Movement de Harlem dans les années 60.

Il suffit d’examiner les noms, les syllabes vedettes conjurants un moment historique révolutionnaire: Sun Ra, Milford Graves, James T. Stewart, Sonia Sanchez, Don L. Lee, Clyde Halisi, Stanley Crouch, Cecil Taylor, Mwanafunzi Katibu, Albert Ayler, Keorapetse ‘Willie’ Kgositsile, Aaron Ibn Pori Pitts, Archie Shepp, Stevie Wonder, Ornette Coleman et plus – et tout cela seulement dans quatre numéros publiés sur seulement deux ans.

La conception graphique à cran de The Cricket’s reflétait son contenu éclectique. Entre ses couvertures criardes, le monde de la culture noire était gravé en blanc et noir tranchant, exploré, interrogé, explosé. Un magazine sur la musique? En quelque sorte. Un magazine littéraire? Cela aussi. Une revue critique? Sans doute. Une intervention philosophique dans la vie de tous les jours? Absolument.

The Cricket intégrait l’énergie de plusieurs musiciens: Sun Ra, le percussioniste Milford Graves, et le pianiste Cecil Taylor sont listés comme conseillers. Poésie et théâtre entremêlés de critiques d’albums et de polémique Black Nationalist. Des activistes-musiciens-écrivains tissaient des vers et de la prose; des poètes-essayistes tentaient de capturer le pouls et l’attitude de la nouvelle musique tout en claironnant le black power et condamnant le racisme blanc. Du point de vue stylistique, leurs mots dans toutes leurs formes incarnaient une sorte de jazz verbal. “Nous voulions un art qui soit aussi noir que notre musique,” se rappelle Baraka. “Une poésie de blues (à la Langston et Sterling); une poésie jazzy; un verset funky empli d’armes explosantes antiracistes et de nouvelle poésie musicale qui crierait et raillerait et attaquerait de son rythme l’ennemi jusqu’à soumission.”

Cependant, après quatre numéros The Cricket fût détruit par le même agenda politique qu’il incarnait. Comme se le dira plus tard Baraka, “Nous nous étions tellement immergés dans son aspect politique [du Black Nationalism] qu’en fait les choses édifiantes comme The Cricket ne furent pas poursuivies…” Alors que de nombreuses publications, allant de The Grackle (mi années 70) de Ron Welburn à Straight No Chaser (1988 – ), continuèrent dans la lancée de The Cricket, personne n’a encore égalé son innovation, sa promiscuité créative et la croyance intense en la possibilité de liberté. Comme Baraka le dit, “La beauté n’a rien à y voir, mais cela en est!”

View (pour voir) une version sommaire du quatrième volume de The Cricket, publié dans Albert Ayler, Holy Ghost, rare & unissued recordings (1962 – 70), 9 CD Spirit Box, 2004.

PEOPLE

Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), A. B. Spellman, Larry Neal, Mwanafunz Katibu , Milford Graves, Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra, Stanley Crouch, Gaston Neal, James T. Stewart’s, Sonia Sanchez, Clyde Halisi, Don L. Lee, Norman Jordan, Ben Caldwell, Mtume, Roger Riggins, Albert Ayler, Askia Muhammed Toure, Willie Kgositile, Ibn Pori, Ishmael Reed.

FAMILY TREE

- The Floating Bear: A Newsletter. (1961-1969) A mimeo magazine delivered by mail. Diane Di Prima & and LeRoi Jones, eds.

- Yugen (1958-1961) LeRoi Jones and Hettie Cohen, eds.

- Liberator (1961 and 1971) Founded by the architect turned full-time activist Dan Watts.

- Freedomways (1961 – 1986)

- Umbra Magazine (1962)

- Afro World (1965)

- The Grackle: Improvised Music in Transition (1976-78). Roger Riggins, James T. Stewart and Ron Welburn, eds.

- Journal of Black Poetry (1966 – 1973) Dingane Joe ed.

RE/SOURCES

- Gennari, John. Blowin’ Hot and Cool: Jazz and Its Critics. University of Chicago Press, 2006. p. 287 – 290.

- Funkhouser, Christopher. “LeRoi Jones, Larry Neal, and the Cricket: Jazz and Poets’ Black Fire”, African American Review, Vol. 37, 2003.

- Komozi Woodard Amiri Baraka Collection, Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African-American Culture and History. Series I: Black Arts Movement, 1961-1998.

- Poet Amiri Baraka on the freedom movement and Black art, The Gainesville Iguana, January 2007.

- Thomas, Lorenzo and Nielsen, Aldon Lynn. Don’t Deny My Name: Words and Music and the Black Intellectual Tradition. University of Michigan Press, 2008, Page 131

- Kalamu ya Salaam. Djali Dialogue with Amiri Baraka, First in a Series of Conversations with Established and Emerging African-American Writers. The Black Collegian Magazine.

- Smethurst, James. Pat Your Foot and Turn the Corner: Amiri Baraka, the Black Arts Movement, and the Poetics of a Popular Avant-Garde; African American Review, Vol. 37, 2003

- Hanson, Michael. Suppose James Brown read Fanon: the Black Arts Movement, cultural nationalism and the failure of popular musical praxis. Popular Music. Cambridge University Press, 2008, 27:341-365