by Akin Adesokan

One is an African writer, or rather one becomes an African writer, it seems, not so much by writing as by winning a prize. Better if the prize is awarded to a work of fiction. Better still if the prize is awarded from Western Europe or North America. Much better still if the winner is young, privileged, and well-spoken, and the author of a first book about “difficult”, “heartbreaking” subject matter written in clear, simple prose.

This state of things has resulted in a situation of endlessly amusing irony, an odd turn of things, of which two paradoxical attitudes are symptomatic.

First, there is the situation in which the writers who are most praised in the international media are also, oddly, the most critical of Western representations of African realities. If one were to take a poll of works of African writers who have attracted the most popular attention in the past ten years, one would discover that it is not so much the highly prized novels or stories themselves, but the statements which these authors make that attract the attention – statements that are deliberately aimed at patronising views of the continent, the cultural basis, in fact, of the very patronage that underwrites the careers of some of these writers.

Binyavanga Wainana’s “How to Write about Africa”, published in a 2005 special issue of Granta titled The View from Africa, is a brilliant joke of a satire that might have been Swiftian had it had the earnestness of Jonathan Swift’s great “Modest Proposal”. The piece has had the singular honour of being “the most forwarded story in Granta history”, as the author himself noted in a commentary published subsequently in Bidoun. You read it once and knew it was clever, knew it would not reward a second reading. The larger problem, however, is that the author found it necessary, even as a joke, to address himself to some general foreign reporter. That it worked, that it generated such great and bizarre discussion, was itself a bad sign.

A close second to this piece, if not indeed the better known, is the 18-minute video of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s famous TED talk, “The Danger of a Single Story.” Adichie’s rhetorical gifts are immense and sedulous, her ability to gauge the emotional level of her audience assured. True, that audience was not a uniformly “Western” one; the video has probably been watched by more African-identified cultural consumers than putative North American or European ones.

But watching that video, and reading the transcript later, I was struck by the simplicity, the powerfully affecting manner in which Adichie calibrated her speech. It did not sound angry. If anything, it was gentle and generous, emphatic without being earnest, appealing to the best in the listener. Ultimately, though, it was a performance, and the targeted audience was the same as Wainana’s: white, liberal, culturally knowing.

These are self-congratulatory rhetorical games, guaranteed to send specifically Western journalists and opinion-makers on liberal guilt-trips. But the games are also guaranteed to conceal the knowledge that African writers can use the same stereotypes self-consciously, and that, as Barry Hannah, talking about Hollywood, noted in a 2010 interview in Harper’s magazine, North American cultural elites regularly turn the same kind of stereotyping on their own societies. Is there a sound more clichéd than a harmonica or an accordion wafting over dusty, rutted roads in a film about the Southern United States? To attack the power of representation in this way is to score a bull’s eye in the short run, but the effect in the long run is to perpetuate that power.

On the contrary, Wainana’s incredibly imaginative first book, One Day I Will Write About This Place, completely displaces any anxieties about selfunderstanding, and it deserves to be read widely and closely. Even if it courts a culturally sophisticated reader invested in well-wrought narratives, it does this with a cleverness light years away from that which informed the writing of the Granta piece.

There is something of a compulsion about the second attitude of African writers. A puzzling compulsion to disavow. This is the spectacular ritual rejection of the label of “African writer”, and the posture of two writers – Pettina Gappah, the author of An Elegy for Easterly, and Olufemi Terry, the 2010 winner of the Caine Prize – captures the spirit of this rejection.

Following the award of the prize to his short story, “Stickfighting Days”, the author published a short piece in Granta (again!) about his “Caine Prize year”. In the preceding year, he had had several encounters with readers of his story who had confronted him with certain expectations on matters of craft which were presented in the vocabulary of social responsibility. Terry felt that the encounters confirmed my sense that there are a great many pitfalls that a so-labeled African writer must avoid. Among these: a preoccupation with authenticity – with subjective realness, with being African – rather than with imaginativeness or breaking new ground; retreading well-worn terrain; and attempting to redress negative news out of the continent by writing stories of upliftment.

Yes.

It must be exasperatingly tiresome to see fiction being read as some sort of sociological blueprint, a commitment piece to correct wrong perceptions, and not all writers would want to pick up that gauntlet. But then Terry concluded his piece by writing, “There is, for me, no African writing, only good writing and bad writing.”

No. No sir. There is African writing, and it could be good or bad. Ayi Kwei Armah’s The Healers is African writing and it is very, very good. First-rate good. The novel could only have been written by someone who consciously identifies as an African writer. Wole Soyinka’s Madmen and Specialists is African writing as pure genius, inspired more by Yoruba oriki than anything else. John Dos Passos’s The 42nd Parallel is North American writing, but not in the way that Thornton Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey is.

Terry also noted that “winning a prize open only to African writers has been vital to my progress as a writer, in allowing me to meet readers of my work as well as offering an opportunity to write what I like.” It is fine to compete for a prize “open only to African writers”, but it is anathema to be called an African writer? OK.

Gappah takes a somewhat different tack. After her first collection of stories, Elegy for Easterly, was awarded the Guardian First Book Award, she gave an interview to the Guardian of UK in which she rejected being labelled an “African writer”. This annoyed many people because, as she later wrote on her blog, “they thought that I was rejecting my black African Nubianness.” She declared, “I am honestly not interested in writing for the edification and education of the West. Nor do I write to correct historical wrongs.”

Yes indeed, again. But is writing for the edification of the West all that an African writer does? Has Ms Gappah paused to reflect on whether the interest in Zimbabwean writers, which began to gain currency in the late 2000s, has to do with other things than good writing? The appealing monstrosity of Robert Mugabe as a brutal black king taking it to the whites, say?

Is NoViolet Bulawayo a better writer than a contemporary writing in Turkish or Korean? Is her subject matter more compelling, and for whom? When there is a special prize in African writing administered from England and partial to prose fiction in English, can any of these questions be ignored or answered satisfactorily?

These two broad attitudes might appear paradoxical, facing what look like opposite directions. In fact, they are going the same way. They make sense only when they are displayed for the attention of the world outside the continent. It is as odd to disavow the tag of “African writer” in Lilongwe as it is to lecture an African-located audience on how to write about the continent.

In all the seductive declamations and disavowals and posturing, some simple facts escape attention.

Marginal peoples and practices on the African continent have a unique appeal, the attraction of novelty. Christianity and Islam largely defeated their African competitors not only because the imperial faiths were transcendental and so forth, but also because they came at times of great cultural upheavals and disaffections. Islam entered West and East Africa with the stealth of a parasite. The harrowing wars set in motion by the insatiable hunger for slaves thoroughly trashed what was left of societies across Africa from the early 18th century on.

Bondsmen, “recaptives”, war prisoners, women, wandering strangers and children marked for ritual cleansing, human sacrifice or ostracism – these were all cultural and social minorities in 19th-century West Africa. Colonialism, commerce and Christianity, opportunistically, came in as redeemers of the innocents. There is a fascinating analogy to be drawn between this aspect of history and the narratives of suffering beloved of African writers.

Sexual minorities, women escaping genital mutilation, rape victims, child soldiers figuring as psychological wrecks, victims of Sharia stoning rescued in the nick of time by a human rights-type of global outrage – these are all good causes to be championed by an external reading public. This reading public, largely white, liberal and female, is also in the habit of raising money and consciousness about Darfur, or championing the cause of education for girls in Afghanistan, just as the Swiss villagers who perceived James Baldwin as a stranger and members of Alice Walker’s church did for African converts in the 1950s.

It is not enough for African writers to write about these things in order to be deemed praise- or prize-worthy; they are also expected to have complementary autobiographies, preferably nastier, stranger than the fictions. Writers buy into them – nothing sells like bad news.

But what African institutions exist as alternatives to the glamorised abjections of “African writing”, which entrench abhorrent misrepresentations and prejudices?

Must the intellectual and artistic ideas by which a society’s worth is measured necessarily come with these strings attached?

In 1989, the Pan-African Writers Association was launched in Accra, with great fanfare. It is expected to award a number of prizes to books by African authors every year. It does no such thing. It has had the same secretary-general since inception. Long live President for Life!

Nigeria’s NLNG Prize for Literature, on the contrary, gives a prize to a work in a different genre every year. It is “the biggest prize in Africa”, the saying goes. But it is also the most problematic: awarding US$100,000.00 to a literary work in a country without vibrant publishing, good distribution, functional libraries or editorial agencies is an act of recognition more misplaced than noble.

But, of course, Nigeria is “the largest country in Africa”.

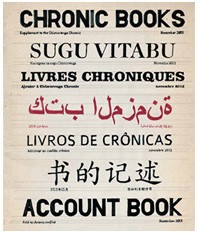

Akin Adesokan’s provocative opinion piece, features in the December 2013 edition of Chronic Books, the books supplement to the Chronic.

Akin Adesokan’s provocative opinion piece, features in the December 2013 edition of Chronic Books, the books supplement to the Chronic.

This issue of Chronic Books includes an interview with Ama Ata Aidoo and a series of discussions with translators. To order a copy (in print or as a PDF) visit our online shop or visit your nearest stockists.

[button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/chimurenga-shop” color=”red”]Order the Chronic[/button]

Akin Adesokan is the author of Roots in the Sky, a novel, and a collection of essays, Postcolonial Artists and Global Aesthetics. He is a contributing editor of Chimurenga.