[hr]

Emeka Ugwu is a Data Analyst who lives in Lagos, Nigeria. He also reviews books at Wawa Book Review.

[hr]

Dear Reader,

To Whom It May Concern.

My name is Emeka Ugwu, I am a Wawa man. I write this letter to inform you about the state of affairs in the country where I was born, from a hamlet in Akegbe-Ugwu, the place my ancestors call home. As I write, Microsoft Word does not recognise either my name or that of my village. Regardless, from my name though, you may already figure I am an Igbo made in Nigeria (not from the American first nation), so I only need add that my country tells me my state of origin is Enugu. My green passport clearly indicates I was born in Port Harcourt, a city where I also feel at home.

I live in Lagos, that beautiful city by the lagoon, a place I also love to call my home. At the time of my birth in the year of my country’s first economic recession, 1981, Enugu, this city of coal buried afoot the Udi plateau, did not exist as a state. It was carved out 25 years ago by one General Ibrahim Babangida. If you asked me in the late 1980s, as my countrymen are wont to for mostly flimsy reasons, I would claim Anambra as my state of origin. So you see, in a way Onitsha is also a place where I am at home whenever I chance a visit.

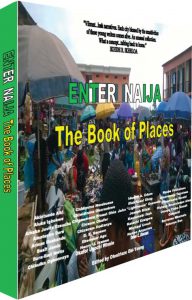

On 1 October 2016, my country celebrated its 56th year of independence. Eighteen days after, I added another year myself. Both these events in a month when Africa celebrates two of her finest and most illustrious sons, Thomas Sankara and Fela Kuti, yield space for one to think about the deeper meaning of home and what it means to leave home in order to discover home. This question is at the centre of Enter Naija: The Book of Places, a new anthology edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young, and released online as an e-book with Brittle Paper.

Enter Naija: The Book of Places is an invitation to engage Nigeria as an idea, which might not yet have materialised, but has at least begun to crystallise as more and more subjects begin to understand their power as citizens. It is a collection of short stories, poems, visual art images, photographs and essays about places that crisscross this specific home, Nigeria, a nation-space that this book’s contributors all feel strongly about. It is a gift. A gesture made from a place of love. The book is free but priceless. It is a gambit not a gambol.

Considering the liberal cosmopolitan worldview that inspires this visionary work, one is inclined to pitch tents with Obi-Young who thinks “of places as people, with layers of distinctness never to be known until known, always retaining their capacity to startle,” if only to invoke an indaba that aims for “eclectic interpretations, full, rounded contemplations of physical features and population characteristics of places” like Kano, Auchi, Ikot Ekpene and Akure.

The young compatriots, who have taken up Obi-Young’s challenge and entered this Naija do not typify your ordinary Nigerian, for whom complaints usually signal strategy not noise. Individually, each stands out as an outlier whose outlook will mark the future. Collectively, they present a strategy to write about home by writing back home, from home. The bulk of them are university students or university graduates, some of whom are engaged in national youth service. Together they posit, as Tanure Ojaide does in his poem, that “It No Longer Matters Where You Live.”

The point is driven home in the story, “Scares on the Other Side of Beauty, or: The Neglected Facts of Ukanafun People” by Iduehe Udom. Here the graduate of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka writes:

“Discussing the culture and traditions of the Ukanafun people, he mentioned Ekpo, Ekong. Ekpe, Utu-ekpe, Akoko, Ekon, Ewa-Ikang Udukghe, Usoro Afa Edia, Usoro Afa Isua, Usoro Ndo and Enin as the most interesting events. He mentioned that trading, fishing, hunting, farming, sculpturing and palm produce hold significant contributions to the slowed-down economy of the town since the civil war depopulated the area and kept it in a situation that many governments have made no efforts to help her recover from.”

If you ignore syntax, or the fact that I know little about these events myself, though I vaguely recall seeing the Ekpe masquerade-costume on a visit to the British Museum once, you will see how the neglected facts evoked in the story’s title help shape discourse about home.

The Ukanafun local government area was created in 1977 from Abak and Opobo divisions of the then Cross-River state. Today Ukanafun is a local government area in Akwa-Ibom, another state that was carved out alongside Enugu in 1991 and, as we learn in Udom’s story, it is a place that is yet to recover from the civil war of 1967–70. It is a place the Annang people call home.

Today under the banner of Independent People of Biafra (IPOB), there is a renewed call for secession by my Igbo people. Where do the Annang stand in relation to this? To understand this slippery slope, we will have to ask how the Annang man remembers Biafra. But first we must comprehend that Naija is home to 250 ethnic groups with 350 languages spread across 37 states.

These days most readers enter Nigeria through the work of my sister, Chimamanda Adichie. In May of 2014, Adichie’s piece, “Hiding From Our Past” and published in The New Yorker, took a dig at the “Nigerian government censors” who were delaying the release of the film adaptation of Half of a Yellow Sun. “The war was the seminal event in Nigeria’s modern history, but I learnt little about it in school,” Adichie wrote, “‘Biafra’ was wrapped in mystery.” She goes on to explain:

“I became haunted by history. I spent years researching and writing Half of a Yellow Sun, a novel about human relationships during the war, centred on a young, privileged woman and her professor lover. It was a deeply personal project based on interviews with family members who were generous enough to mine their pain, yet I knew that it would, for many Nigerians of my generation, be as much history as literature.”

Adichie criticises the film’s censorship as “absurd”: “[S]ecurity operatives, uninformed and alert, gathered in a room watching a romantic film – the censor’s action is more disappointing than surprising, because it is a part of a larger Nigerian political culture that is steeped in denial, in looking away.” For my part, I find it rather curious that, in speaking out against censorship, she censors quite a significant bit of the Biafran impasse. Hiding behind her own past she looks away from the Igbo domination of Annang people.

Her working premise assumes ostensibly that since the “massacres in northern Nigeria” which targeted only “south-eastern Igbo people” inevitably led to a secession, the Efik, Ijaw, Ibibio and Itsekiri man relinquished his own identity, so it is okay to lump them together as Igbo people who share a common grievance. Ken Saro-Wiwa must be choking on a pipe in his grave. Remind me, what exactly the Ogoni man was on about in his book, On a Darkling Plain? My own sense is that truth sadly was the first casualty of the Nigerian civil war.

Enter Naija: The Book of Places invites readers to enter this impasse by taking a new approach. One that looks ahead instead of dwelling on the past. One that is inclusive instead of selective. In a time of Boko Haram, of increased hostilities in creeks of the Niger Delta, and of the scourge of cattle herdsmen, the question that reverberates most strongly for me is: how does Nigeria retreat in order to advance. Inertia?

Adichie suggests remembering by memorialising. She suggests building a memorial, and I concur but insist, one for all those who lost their lives during the civil war. Touched by the pain of the Annang people, who inhabit the landspace Udom illumines, I am drawn to more didactic approaches because, as physicist Cesar Hildago asserts in Why Information Grows: for complex systems like Nigeria the message is not its meaning. Yet the difference betwixt societies depends on how they order information. Nigeria is as weak as the weakest link in its network of people(s).

To bring my concern closer home, it is only fair considering I have appropriated Obi Egbuna’s Diary of a Homeless Prodigal as title of my own letter for an entirely selfish purpose. This allows me to place my writing into a network of other writing. It also allows me to edge this reflection towards his thoughts as expressed in one letter, “Meeting My People”. Egbuna questions hard: “How can I explain Che’s meaning that ten city intellectuals are worth less than one farmer in the village, that the African problem can never be solved by the African ‘Elite’ because the African ‘Elite’ is part of the problem?” The answer is not simple but there is an answer: organise and build.

Enter Naija: The Book of Places offers an entry point, one way of organising and building. It situates multiple places within a deeply fractured nation space wherein Egbuna’s searching question seeks an answer. It answers by sending messages about the human condition and lived experience so that we, the reader, can mine them for meaning fleshed out of information about the plight of people(s). It allows us to join the conversation by assembling our own answers. It shows how irrespective of ethnicity/religion, elite interests lie only in the appropriation of wealth and labour for the consolidation of state power. It shows that the solution to our problems resides in our ability to build expansive and inclusive social networks that allow us to leave home in order to discover home.

Thank you for your attention and time. I urge you, enter Naija, come see where we are going.

Prodigally Yours.

[hr]

This piece appears in the Chronic (April 2017). An edition which aims to complicate the questions raised by food insecurity, to cook and serve them differently.

Food is largely presented as scarcity, lack, loss – Africa’s always desperate exceptionalism or exceptional desperation or whatever. In this issue, we put food back on the table: to restore the interdependence between the mouth that eats and the mouth that speaks, and to delve deeper into the subtle tactics of resistance and private practices that make food both a subversive art and a site of pleasure.

To purchase in print or as a PDF head to our online shop, or get copies from your nearest dealer.

[button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/chimurengashop” color=”red”]Buy the Chronic[/button][button link=”http://www.chimurenga.co.za/subscribe” color=”red”]Subscribe[/button][hr]